Several people have been asking questions about obtaining permission to reprint. Instead of taking you through the steps, I’m going to tell you a true story about a particularly thorny permissions problem I ran into myself.

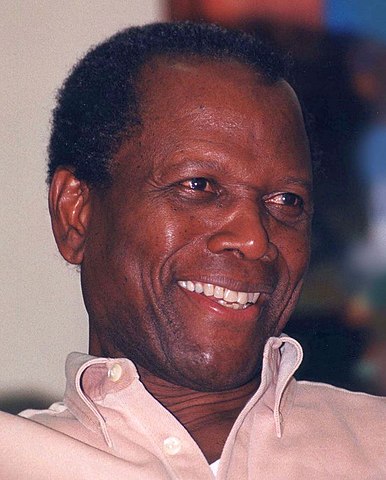

Sidney Poitier – the superb actor who died last week – is the hero of this story.

Some years ago I wrote a study skills textbook for college students. Early in the writing process I spent several Saturday mornings in the biography section of local library, scanning the early chapters to look for true stories from famous people about their early learning experiences.

I struck gold with actor Sidney Poitier’s memoir This Life. (Later he wrote another one.) Poitier described arriving in New York City from the Bahamas as an ambitious 17-year-old with little education and limited funds. He supported himself washing dishes and dreamed of becoming an actor – but he couldn’t read well enough to get through an audition.

A Jewish waiter saw Poitier struggling to read a newspaper and offered to help. Years later, Poitier vividly remembered those reading lessons. One especially helpful skill was learning how to figure out the meaning of a word from the context. It was an impressive story, well told, and I gladly paid the Alfred A. Knopf publishing company $100 for permission to copy Poitier’s story in my chapter on reading.

Happily, my study skills book eventually went into a second edition. But not so happily, I had to redo all the permissions, and the Poitier selection became a problem. Knopf no longer owned the rights – they had been transferred to Poitier’s law firm.

In those pre-Internet days, it was no small feat to learn who Poitier’s lawyers were – and that was only the beginning of my struggles. The permissions fee was too small for the firm to be concerned about. I called multiple times, explaining that my book was about to go into production and I desperately need that permission form. Each time they promised to take care of it – and promptly forgot.

One morning I went through my spiel for about the twentieth time (it seemed that someone different answered the phone whenever I called). I was put on hold. After several minutes, someone came on the line and asked what I wanted.

I was getting fed up with telling my story over and over – but common sense won the day, and I politely explained what I wanted.

“Can you tell me more?” the voice asked. And suddenly it dawned on me that I was talking to Poitier himself. The attorney’s office had patched my call through to his home phone.

I explained how impressed I’d been with his story about the dishwasher and newspaper lessons. Poitier gave me his fax number and asked me to send the chapter to him so he could see what I’d be doing with his story.

Three days later I opened my mailbox and found the signed permission form there. He was the only author who didn’t ask for a permissions fee.

A great and generous man.

(Because I’ve been hearing so many questions about modes of development, I’m adding a postscript. If I’d described the permission steps in a general way, this would have been a process article. Today I’ve told you a story that happened once, so it’s a narrative.)